By: Melissa Bank Stepno, President & CEO

Let’s channel Paul Simon for a moment and talk about shoes. That’s probably not the lead-in that you expect from a blog post that’s supposed to be about philanthropy. But, I promise you it is!

Let’s channel Paul Simon for a moment and talk about shoes. That’s probably not the lead-in that you expect from a blog post that’s supposed to be about philanthropy. But, I promise you it is!

In Simon’s song Diamonds on the Soles of her Shoes, he sings about a woman that is so rich that she literally has diamonds on the soles of her shoes.

Or, if you would prefer, let’s remember Dorothy from the Wizard of Oz, who wore what is perhaps the most famous pair of shoes – Ruby Slippers.

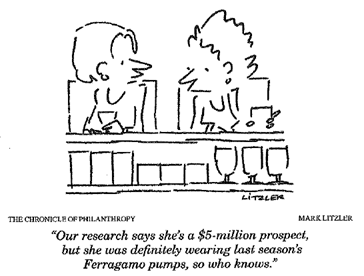

Closer to our work, I am reminded frequently of this very old cartoon from the Chronicle of Philanthropy. I liked it so much that I clipped it out of the printed publication more than a decade ago and I still have it on my desk:

Maybe Mark Litzler, the cartoonist, heard the same real-life story that I heard, told by a salesperson who was on a trip to see a potential client with the CEO of the public company where he worked. As he tells it, the evening before “the Big Meeting,” the CEO broke one of his shoes and wasn’t traveling with a spare pair.

I get it – stuff happens when you travel. We’ve all been there.

There’s an HBGer on our team who broke her shoe at the beginning of our annual retreat earlier this year. She took an “emergency Uber” to the closest DSW to buy herself a pair of new shoes.

I was once walking down the street and had the strap of my sandal snap off. Conveniently, I had just walked past an independent shoe store. I immediately turned around, walked into the store, and bought myself a new pair of shoes.

I also realize that the luxury of “just buying a new pair of shoes” is not something that everyone can afford to do. But, let’s get back to the public company CEO for a moment.

At most organizations, finding a public company insider is a clear path to major gift prospect potential. At the very least, I would argue that every single Insider could “afford” to buy a new pair of shoes.

So, what did this CEO purchase? He didn’t.

What he did was reach out to the hotel’s maintenance department and ask for some duct tape, which he used to hold his shoe together. The next morning, the CEO and the salesperson arrived at “the Big Meeting” with one shoe clearly held together with duct tape.

I was just as surprised as you might be when I first heard this story. Or, perhaps, you aren’t surprised at all?

My point is that whether a person is wearing last season’s Ferragamo shoes* or has duct tape holding their shoe together, the way people present themselves with or without materialistic luxuries could have very little to do with their philanthropic capacity.

*Side bar: for those of you unfamiliar with Ferragamo shoes, a quick check of their website as I am writing this shows that the least expensive pair of shoes they are currently selling is $565, with the most expensive being $2,900.

In the book The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel, the author lays out 20 principles that he believes are the most important factors related to … well … the psychology of money. Or, to put it another way, how a person’s psychology, philosophy, background, goals, circumstances and behavior can have a tremendous impact on their financial situation.

One chapter focuses on “Wealth is What You Don’t See” with the subtitle “spending money to show people how much money you have is the fastest way to have less money.” Now, I’m not suggesting that my colleague and I shouldn’t have bought new shoes when ours broke at an inopportune time. But, keep in mind that neither one of us bought “emergency” Feragamos either!

Housel uses cars, not shoes, to make his point and shares a story from when he was a valet at a hotel in Los Angeles. A frequent guest who typically arrived in a Ferrari (major gift prospect?) showed up one day in a Honda. When asked about it, the guest told Housel that the Ferrari was repossessed after defaulting on a car loan (No, probably not a major gift prospect).

Housel states: “we tend to judge wealth by what we see, because that’s the information we have in front of us. We can’t see people’s bank accounts or brokerage statements. So, we rely on outward appearances to gauge financial success. Cars. Homes. Instagram photos.” Maybe even shoes.

Housel isn’t advocating for this approach. Rather, the chapter is designed to completely rebuke it. His point is that the people who are the wealthiest are often those that don’t buy the expensive car, or the luxury shoes, or are dripping with diamonds. The wealthiest are often the most outwardly modest. And those who are the most “showy” are sometimes the most leveraged with no disposal income or invested assets to spare.

While not a book about philanthropy, Housel proves the point of why more sophisticated prospect research and analysis is needed to estimate what someone’s philanthropic capacity might be. No, prospect development professionals still can’t see a person’s bank account balance or brokerage statement. But we certainly have the tools and resources to be more sophisticated than relying on materialistic or outward appearances.

This also reminds us that even with the best prospect research techniques, sometimes a person’s true capacity will elude us. We’ve all heard stories of the surprise multi-million-dollar bequest that shows up after a person with a seemingly humble background passes away. The schoolteacher. The nurse. The janitor. The gas station attendant.

For Housel, his example comes from a gentleman by the name of Ronald Read, who was both a gas station attendant and a janitor. Yet, when he died, his will contained two bequests totaling more than $6 million. At the time, the bequests were the largest gifts that the Brooks Memorial Library and Brattleboro Memorial Hospital, both in Read’s local VT community, had ever received.

How did Read do it? He lived frugally and invested very well. We don’t know if he used duct tape on his shoes but we do know that he held his winter coat together with a safety pin and even at 90+ years old, parked his 14-year old Toyota Yaris further away than he had to just to save the cost of a parking meter.

The moral of these stories is simple: the way people present themselves, with or without materialistic luxuries, could have very little to do with their philanthropic capacity. As a profession focused on prospect strategy and fundraising intelligence, it serves as serves as a very distinct reminder for us. While in rare instances some prospects will surprise us with assets that we will never be able to find, more importantly, it demonstrates why the work that we do is so important – our organizations can’t afford (literally) to make capacity assumptions based on solely on a person’s outward appearance.

***

Image Credit 1: Smithsonian Institution, Ruby Slippers, https://www.si.edu/object/ruby-slippers-worn-judy-garland-dorothy-wizard-oz:nmah_670130

Image Credit 2: Mark Litzler, Chronicle of Philanthropy, circa 2014