By: Amy Caldarelli, Consultant

Today I’m going to do a deep dive with you all on something I never anticipated caring or knowing anything about but that has become a throughline of my entire adult professional life: property values. (When I told my husband I’d be writing a blog post for work, he said, “Is it going to be about property values?” I nodded excitedly, and he said, “Of course it is.”)

Indulge me for a minute while I explain how I ended up here. When I graduated with a master’s degree in 20th-century art and politics in 2009, the first job I got was working for a regional galleries association. The next job I got was at a property tax law firm. In my mind, the first one would end up being formative in the direction of my career. To my surprise, it was the second one that did. Do I know a lot about art as a wealth indicator because of my time studying art? No; what I can tell you about art mostly has to do with its cultural relevance and mechanism for dissidence as well as community and identity formation, particularly during times of social and political upheaval. Do I know a lot about real estate as a wealth indicator based on my time preparing case evidence for property tax appeals? Well, yes. I do.

This is why I’d like to dig into a couple questions that our president and CEO, Melissa Bank Stepno, posed in her post last year, “The Real Estate Quagmire,” and tantalizingly suggested could each produce its own blog post. Just as she focused on two questions in that post, I’ll focus on another pair here—two of the most basic we can ask:

- How are you determining the “value” of the property, and which “value” are you using?

- Where is the property located geographically?

I want to state right up front: I’m not going to explore either of these topics comprehensively, and I’m not going to tell you which property value you should use. What I am going to do is review some of the basics of property value types and how the location of a property can affect which value of a property makes the most sense to use.

Assessed vs. Market Value

For the purposes of a prospect researcher, at least, there are two main categories of property values to consider: (1) the assessed value that a local township or county assessor determines to calculate real estate/property taxes, and (2) the market value that a property could be expected to—or maybe even recently did—sell for on open market (fair market value).

The latter can be found in all kinds of sources: Zillow’s Zestimate is perhaps best known (or notorious, depending on your perspective.) Redfin, Trulia, and Cotality (formerly CoreLogic, and which is a data source for vendor tools like iWave and WealthEngine), to name a few, have their own proprietary algorithms to determine up-to-date fair market value estimates for real estate.

Assessed values are both a little more, and a little less, straightforward. Any given parcel of real estate has only one assessed value. This type of property value isn’t an estimate that depends on which data source you’re using, but a verifiable number that typically changes, at most, once a year. What’s less straightforward is… well, pretty much everything else.

Assessed Values: Terminology and Multipliers

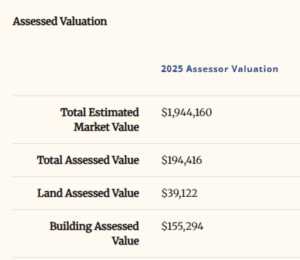

First, there’s the issue of the term “assessed value.” In many jurisdictions, what appears on a tax bill and in public records as the “assessed value” represents only a literal fraction of what the local assessor has determined a property’s fair market value to be. Take Cook County, Illinois, for example, where residential properties are assessed at 10% of what the local assessor calculates a home’s market value to be:

In this case, the local assessor and the tax bill would say the property’s “assessed value” is $194,416, but the “assessed value” a prospect researcher would be interested in is the one the county/township assessor and tax bill are calling a “market value”: $1,944,160.

Moreover, once you know about this assessment-as-a-fraction-of-market-value business, there’s the issue of what that fraction/percentage is, exactly. Staying in Cook County, remember I said residential properties are assessed at 10% of the local assessor’s market value determination? Well, so are vacant land parcels, but commercial and industrial properties are assessed at 25% of market value, and not-for-profit properties are assessed at 20%. And is that the same for the rest of Illinois? [Sigh]… of course not. Outside of Cook County, real estate in Illinois—regardless of use type/class—is assessed at 33.3% of the local county/township assessor’s calculated market value. Looking nationwide, there are enough different multipliers for jurisdictions across the U.S. that there are resources dedicated solely to cataloguing them.

Assessed Values: Policy Factors

California

In some jurisdictions, assessed value may have little to no correlation at all with a property’s current fair market value, or what it would sell for if put on the market today. The most extreme example of this is in California, due to the state’s Proposition 13. Some readers may lean back in their chair, fold their hands together and say, “Well of course, Prop. 13.” For those who don’t: Proposition 13 is a property tax limitation initiative that passed in California in 1978. The California State Board of Equalization explains the initiative and its effects:

Under Proposition 13, properties are reassessed to current market value only upon a change in ownership or completion of new construction (called the base year value). In addition, Proposition 13 generally limits annual increases in the base year value of real property to no more than 2 percent, except when property changes ownership or undergoes new construction.

What this means is that assessed values for California homes can’t go up by more than 2% each year in most circumstances, regardless of how much the home’s market value may have risen over that time. Property owners who purchased their home decades ago “tend to have markedly lower tax liability than recent purchasers,” making recency of purchase a key factor in a California homeowner’s tax bill. It also means that California properties don’t operate on a market value-based property tax system but one that is essentially “acquisition value-based.”

I’ll move on from California in a minute, but it’s worth mentioning one more complexity to California property taxes: “portability” provisions. Under some conditions, California homeowners can transfer the taxable value of a residence, including:

- When transferring a principal residence between parents and children or between grandparents and grandchildren when both qualifying parents are deceased;

- In instances where people over the age of 55 or who are severely and permanently disabled replace their primary residence with a newly purchased or constructed home;

- As a disaster relief measure, allowing transfer of the taxable value of a principal residence substantially damaged or destroyed by wildfire or natural disaster to a replacement residence located anywhere in California.

(These details aren’t necessarily crucial to understanding assessed values, but I’ve certainly come across instances where about these provisions have explained what seemed to be a mystifying difference between the assessed and market values of a prospect’s relatively recently-purchased home.)

… And Beyond California

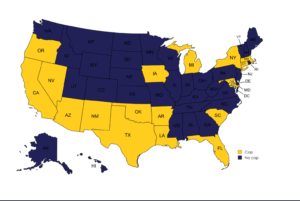

While California has the strictest one, they are not the only state to have a cap on assessed value increases. I’ll spare an in-depth look here at the particulars of other states’ assessment increase limitations, but will include a map published by MOST Policy Initiative that helpfully illustrates which states do and do not have such a limit:

Assets vs. Lifestyle Indicators

To layer in some timely context, the Tax Foundation points out found that, from 2020-2024, property values in the U.S. rose almost 27% faster than inflation and points out that when property values surge, “property owners may be wealthier on paper due to the appreciation of their property value, [but] their income flows and ability to pay higher taxes may not have risen proportionally.” This is essentially the crux of why both assessed and market values are helpful to know and consider when evaluating a prospect’s capacity: it’s a reminder that, with real estate, a market value can show you a fast-appreciating asset, but a property’s assessed value and tax bill may say more about what’s happening to a cost-of-living expense for its owner.

Property Values Aren’t Universal. They’re Local.

For some properties, neither Zillow’s Zestimate nor the assessed value you find in public records seems to make sense. In particular, I’m thinking about certain multi-unit residential properties like co-ops, especially in New York City. I bring this up to make my final point about how to determine which property value(s) to use: it really, really depends on where the real estate is located. Property location can affect not just what’s happening with its market value and how its assessed value is calculated, but also what kind of data is available and relevant to consider.

Bottom Line

So, what should you look for when determining which value to use? Well, first, to get this out of the way: your own organization’s policy, if they have one. I’m not here to shake up any hard-won consensus your organization has come to, just to help make sense of some of the confusion that can exist around property values. Beyond that, a few of the most important questions to ask yourself if you’re trying to decide which value to use:

- What’s available for that property?

- Are there any significant anomalies for that property or area that could affect how local values are determined?

- Does something about the value look… off?

In the end, I always want to be as accurate as possible but also try to keep in mind I’m not trying to sell this property for the prospect, nor am I sending anyone their tax bill. Within reason, slightly over-/under-estimating a property’s value is not going to make or break its accuracy as a wealth indicator. This is where the art comes back in: the part that isn’t about numbers but about interpretation and context, about recognizing property value as a piece of a larger picture of a prospect’s wealth. That’s also what turns data into insight.